When Borders Changed Forever

December 16, 1971, stands etched in the collective memory of the Indian subcontinent as a date that fundamentally reshaped South Asian history. It was on this day that hostilities between India and Pakistan formally ceased, culminating in one of the most decisive military victories of the post–Second World War era. More significantly, it marked the emergence of Bangladesh as an independent nation after years of political neglect, cultural suppression, and brutal military repression in what was then East Pakistan. For India, December 16 is observed as Vijay Diwas—a day that honours the courage, discipline, and sacrifice of its armed forces. For Bangladesh, it is Victory Day, symbolising liberation, dignity, and the hard-won right to self-determination.

The events of 1971 cannot be understood merely as a conventional war between two neighbouring states. They were the culmination of deep-rooted political, cultural, and economic contradictions embedded in the creation of Pakistan itself in 1947. The surrender of nearly 93,000 Pakistani soldiers before the combined forces of the Indian Army and the Mukti Bahini in Dhaka was not just a battlefield outcome; it was the collapse of an unjust political arrangement and the triumph of a people’s struggle against systemic oppression.

A Nation Divided by Geography and Power

When Pakistan was carved out of British India in 1947, it was born with a structural flaw that would later prove fatal. The country consisted of two wings—West Pakistan and East Pakistan—separated by more than 1,600 kilometres of Indian territory. While East Pakistan had a larger population, political power, military authority, and economic resources remained overwhelmingly concentrated in West Pakistan.

The people of East Pakistan, predominantly Bengali-speaking, soon found themselves treated as second-class citizens within their own country. Urdu was imposed as the national language despite the fact that Bengali was spoken by a majority of Pakistan’s population. Economic policies disproportionately favoured West Pakistan, leading to stark disparities in development, employment, and infrastructure. Revenues generated from East Pakistan, particularly through jute exports, were largely invested in the western wing, deepening resentment and alienation in the east.

Over the years, demands for autonomy grew stronger. The 1952 Language Movement, in which students were killed while protesting for the recognition of Bengali as a state language, became an early symbol of resistance. By the 1960s, under the leadership of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and the Awami League, the demand had evolved into a call for meaningful self-rule within a federal structure.

The 1970 Election and the Breakdown of Democracy

The turning point came with Pakistan’s first general elections in December 1970. The Awami League won a landslide victory, securing an absolute majority in the National Assembly—primarily on the strength of votes from East Pakistan. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was constitutionally entitled to form the government of Pakistan.

However, the military and political elite of West Pakistan refused to transfer power. The prospect of a Bengali leader governing Pakistan was unacceptable to the ruling establishment. Negotiations were delayed, the National Assembly session was postponed, and political tensions escalated rapidly. What followed was not political compromise, but brute force.

On the night of March 25, 1971, the Pakistan Army launched Operation Searchlight, a systematic campaign to crush dissent in East Pakistan. Universities, residential areas, and political strongholds were targeted. Intellectuals, students, journalists, and members of the Hindu minority were singled out. The violence unleashed was unprecedented in scale and cruelty.

Genocide, Resistance, and the Refugee Crisis

The military crackdown led to mass killings, widespread sexual violence, and the destruction of entire villages. While estimates vary, historians agree that hundreds of thousands—possibly millions—of civilians were killed in the months that followed. The humanitarian catastrophe triggered one of the largest refugee crises of the 20th century.

By mid-1971, nearly 10 million refugees—mostly women, children, and the elderly—had fled into India, seeking shelter in West Bengal, Tripura, Assam, and Bihar. The sudden influx placed enormous strain on India’s economy, administration, and social fabric. Refugee camps struggled with shortages of food, medicine, and sanitation, while the risk of disease outbreaks loomed large.

India initially attempted to address the crisis through diplomatic channels. The government, led by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, appealed to the international community to intervene and pressure Pakistan to stop the atrocities. However, global response remained muted, constrained by Cold War politics and strategic alliances. The United States and China continued to support Pakistan, viewing it as a geopolitical ally, while the plight of the Bengali population failed to translate into decisive international action.

India’s Strategic Calculus and Moral Imperative

As the refugee crisis worsened and border skirmishes intensified, India’s options narrowed. The situation was no longer merely a humanitarian concern; it had become a direct threat to national security and regional stability. Supporting the Bengali resistance was both a moral responsibility and a strategic necessity.

India began extending covert assistance to the Mukti Bahini—the Bangladeshi liberation forces composed of defected soldiers, volunteers, and civilians. Training camps were set up, logistical support was provided, and coordination between Indian forces and the Mukti Bahini gradually deepened. At the same time, India worked diplomatically to build international support, most notably securing a Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Cooperation with the Soviet Union in August 1971, which helped counterbalance US and Chinese backing for Pakistan.

The inevitability of full-scale war became clear by late 1971. Pakistan, anticipating Indian intervention in the east, attempted to seize the initiative by launching air strikes on Indian airfields in the western sector on December 3, 1971. This act formally brought India into the war.

What followed was one of the shortest yet most decisive wars in modern history. Indian military strategy in the eastern theatre was marked by speed, coordination, and clarity of objective. Rather than engaging in prolonged battles for territory, the Indian Army focused on rapidly isolating Dhaka, the political and military nerve centre of East Pakistan.

The Eastern Command, under Lieutenant General Jagjit Singh Aurora, executed a bold multi-pronged advance, bypassing heavily fortified positions and cutting off Pakistani supply lines. The Indian Air Force achieved air superiority within days, crippling Pakistani communication and transport networks. The Indian Navy played a crucial role by blockading East Pakistan’s ports, preventing reinforcements or escape by sea.

Equally important was the role of the Mukti Bahini, whose intimate knowledge of the terrain and popular support proved invaluable. Their guerrilla operations disrupted Pakistani movements, gathered intelligence, and maintained pressure from within. The war was not just a clash of armies but a coordinated liberation campaign involving soldiers and civilians alike.

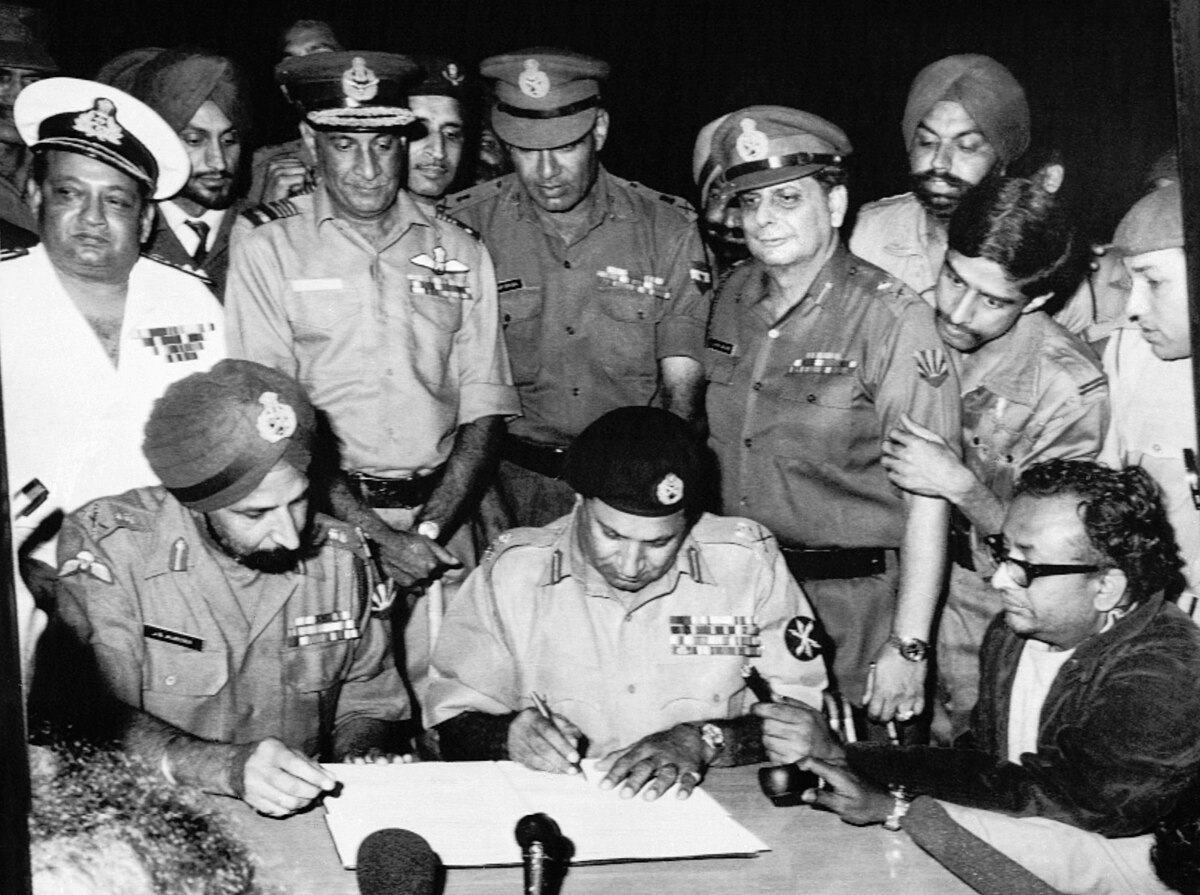

Surrender in Dhaka

By mid-December, the outcome was inevitable. Pakistani forces in East Pakistan were exhausted, isolated, and demoralised. With Dhaka surrounded and no realistic prospect of relief, Lieutenant General A.A.K. Niazi agreed to surrender.

On December 16, 1971, at the Racecourse Ground in Dhaka, Niazi signed the Instrument of Surrender in the presence of Lieutenant General Aurora. Approximately 93,000 Pakistani soldiers and officers laid down their arms, making it the largest military surrender since the end of World War II. The moment was broadcast across the world, symbolising not only India’s decisive victory but also the end of Pakistan’s authority in the east.

For the people of Bangladesh, it was the culmination of a long and painful struggle. For India, it was a moment of immense national pride, reflecting the professionalism of its armed forces and the political resolve of its leadership.

Birth of Bangladesh and a New Regional Reality

The surrender paved the way for the formal establishment of Bangladesh as an independent nation. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who had been imprisoned in West Pakistan during the war, was released and returned to a hero’s welcome. Bangladesh faced enormous challenges in the aftermath—war-ravaged infrastructure, economic devastation, and the trauma of genocide—but independence provided the foundation for rebuilding on its own terms.

For South Asia, the creation of Bangladesh fundamentally altered the regional balance. Pakistan emerged from the war politically humiliated and territorially diminished, prompting internal introspection and eventual political change. India, on the other hand, established itself as the pre-eminent regional power, capable not only of military success but also of shaping regional outcomes.

The war also reinforced important lessons in international relations. It demonstrated the limits of great-power intervention when confronted with determined regional action backed by popular legitimacy. Despite diplomatic pressure and military posturing by external powers, the outcome in 1971 was decided on the ground by the resolve of the Indian military and the Bengali people.

Vijay Diwas: Memory, Sacrifice, and Responsibility

In India, December 16 is commemorated as Vijay Diwas to honour the soldiers who fought and sacrificed their lives in the 1971 war. Memorials, wreath-laying ceremonies, and tributes serve as reminders of the cost of peace and the responsibilities that come with power. The war claimed the lives of thousands of Indian soldiers, whose bravery ensured not only a military victory but also the liberation of millions from oppression.

Beyond military achievement, Vijay Diwas carries a deeper ethical dimension. India’s intervention in 1971 is often cited as a rare example where strategic interest and humanitarian responsibility converged. The war reaffirmed the principle that sovereignty cannot be a shield for mass atrocities and that regional stability is inseparable from human dignity.

More than five decades later, December 16 continues to resonate differently in India and Bangladesh, yet its core significance remains shared. For Bangladesh, Victory Day is a reaffirmation of national identity forged through sacrifice. For India, it is a reminder of a moment when decisive leadership, military professionalism, and moral clarity converged.

The India–Bangladesh relationship has evolved significantly since 1971, encompassing cooperation in trade, connectivity, water sharing, and security. While challenges and disagreements persist, the shared legacy of 1971 remains a powerful foundation for mutual respect and partnership.

A Date That Changed History

December 16, 1971, was not merely the end of a war; it was the beginning of a new chapter in South Asian history. It marked the collapse of an unjust political order, the birth of a new nation, and the assertion of India’s role as a decisive regional actor. The events of that day continue to shape political narratives, national identities, and regional dynamics even today.

Remembering December 16 is not only about celebrating victory. It is about acknowledging suffering, honouring sacrifice, and reaffirming the values of justice, self-determination, and human dignity. In the pages of history, the date stands as a testament to the idea that when the will of a people aligns with principled action, even the most entrenched structures of oppression can be dismantled.

2 days, 11 hours ago

2 days, 11 hours ago

[[comment.comment_text]]