D.D. Kosambi: Revolutionizing Indian Historiography with a Materialist Lens

The following article is a tribute to the great polymath and historian, D.D. Kosambi, on his 58th death anniversary (29 June). Professor Kosambi was instrumental in radically changing people’s perception as well as reading and writing of Indian history, which for a long period, under the British colonial historians’ impact, was a sheer narration of the rise and fall of dynasties —EW

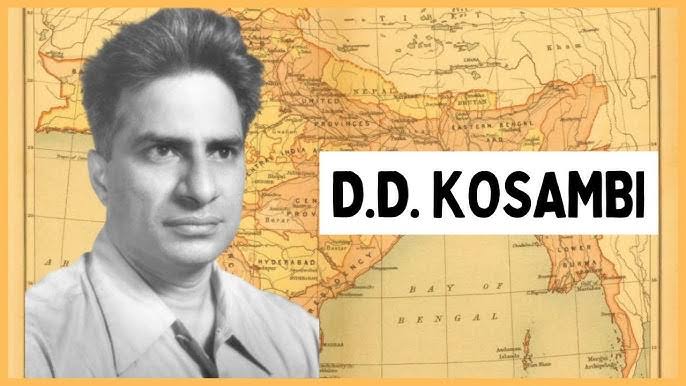

On June 29, 1966, India lost one of its most formidable intellectual giants, Damodar Dharmananda Kosambi, who passed away at 58. A polymath renowned as a mathematician, linguist, and historian, Kosambi’s contributions to Indian historiography remain unparalleled. His revolutionary approach, blending Marxist methodology with rigorous empirical research and an interdisciplinary perspective, redefined how Indian history is studied and understood. This tribute, marking his death anniversary, explores Kosambi’s transformative impact on the writing of Indian history, highlighting his innovative methodologies and enduring legacy.

Redefining the Scope of Indian History

Kosambi challenged the conventional framework of Indian historiography, which traditionally segmented history into rigid categories of Ancient, Medieval, and Modern periods. He argued that such periodisation oversimplified the complex evolution of Indian society. Instead, Kosambi proposed a dynamic approach that emphasised the interconnectedness of historical periods, focusing on the material conditions and social transformations that shaped them. His seminal works, such as An Introduction to the Study of Indian History (1956) and The Culture and Civilisation of Ancient India in Historical Outline (1965), underscored the importance of examining the “means and relations of production” as drivers of historical change.

By shifting the focus from dynastic narratives to socioeconomic structures, Kosambi brought a fresh perspective to Indian history. He analysed how agricultural practices, trade, and technology influenced societal development, offering a more nuanced understanding of India’s past. His rejection of Eurocentric historical models, which often imposed foreign frameworks on Indian contexts, marked a significant departure from colonial historiography.

A Marxist Approach with Indian Sensibilities

Kosambi’s adoption of Marxist methodology was neither dogmatic nor deterministic. While he drew on Marxist concepts to analyse class structures and economic systems, he adapted them to suit the unique characteristics of Indian history. Unlike traditional Marxist historians who might have sought a universal model of historical progression, Kosambi rejected the notion of a uniform “slavery phase” in India. Instead, he traced the evolution of caste society, which he saw as a defining feature of Indian social organisation.

Kosambi’s analysis of feudalism in India, spanning the Gupta to Mughal periods, was equally nuanced. He acknowledged feudal structures but emphasised their distinct Indian characteristics, such as the role of caste and village economies. His insistence on grounding Marxist theory in empirical evidence—through textual analysis, archaeological data, and numismatic studies—set him apart from his contemporaries. For instance, his work on the Arthaśāstra, the ancient Indian treatise on statecraft, illuminated the economic and social realities of the Mauryan period, revealing the interplay of power, trade, and governance.

Fieldwork and the “Folk Present”

One of Kosambi’s most enduring contributions was his emphasis on fieldwork and ethnographic research as essential tools for historians. He believed that understanding the “folk present”—the lived realities of contemporary tribal and rural communities—was crucial for interpreting India’s historical continuity. By studying village life, oral traditions, and surviving cultural practices, Kosambi connected the past with the present, uncovering threads of continuity that written records alone could not reveal.

His extensive fieldwork across India allowed him to observe firsthand the social and economic structures of rural and tribal societies. For example, his studies of tribal communities provided insights into pre-modern social formations, which he used to reconstruct ancient Indian history. This approach not only enriched his historical narratives but also challenged the elitist focus of traditional historiography, which often prioritized courtly records over the lives of ordinary people.

An Interdisciplinary Pioneer

Kosambi’s interdisciplinary approach was a hallmark of his scholarship. He drew on diverse fields such as linguistics, numismatics, archaeology, and anthropology to construct a holistic picture of India’s past. His etymological analysis of Sanskrit texts, for instance, enabled him to reconstruct the social and cultural contexts of ancient India. By examining the evolution of words and their meanings, Kosambi uncovered insights into societal structures and practices that were often absent from conventional historical sources.

Kosambi’s work on ancient Indian coinage further exemplified his innovative methods. Kosambi conducted statistical analyses of coin weights to understand economic systems and trade networks, demonstrating a scientific rigor that was rare among historians of his time. This meticulous approach allowed him to challenge assumptions about ancient Indian commerce and highlight the material conditions that underpinned economic life.

Challenging Romanticized Narratives

Kosambi was unafraid to question romanticized views of Indian civilization, which often portrayed it as a harmonious and spiritually advanced society. Instead, he emphasised the realities of social inequalities, class divisions, and caste hierarchies. His materialist lens revealed how economic systems, such as the development of coinage and trade, shaped social structures and power dynamics. For instance, his analysis of the Mauryan economy through the Arthaśāstra highlighted the exploitation inherent in ancient taxation systems and the centralisation of state power.

By focusing on the lives of ordinary people—peasants, artisans, and marginalised groups—Kosambi shifted the historiographical spotlight away from kings and elites. His work exposed the contradictions within Indian society, such as the coexistence of advanced philosophical traditions with stark social inequities. This critical perspective made his scholarship both groundbreaking and controversial, as it challenged nationalist narratives that sought to glorify India’s past.

Kosambi’s contributions were not without personal cost. His tenure at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR), where he served for 16 years, ended in 1962 due to disputes with its director, Homi Bhabha. The conflict, rooted in ideological and administrative differences, led to Kosambi’s dismissal, a loss for the institute and the broader academic community. Despite this setback, Kosambi continued his research independently, producing works that remain foundational to Indian historiography.

Beyond his scholarly contributions, Kosambi’s legacy lies in his ability to inspire future generations of historians. His insistence on rigorous research, interdisciplinary methods, and a focus on material realities paved the way for modern Indian historiography. Scholars like Romila Thapar and Irfan Habib have acknowledged Kosambi’s influence in shaping a more scientific and socially engaged approach to history.

Kosambi’s Enduring Relevance

As we commemorate Kosambi’s 58th death anniversary, his work remains strikingly relevant. In an era where history is often politicised or reduced to simplistic narratives, Kosambi’s emphasis on evidence-based, interdisciplinary research serves as a reminder of the historian’s responsibility to uncover truth. His focus on the “folk present” resonates with contemporary efforts to include marginalised voices in historical narratives, while his materialist approach offers a framework for understanding the socioeconomic forces that continue to shape India.

Kosambi’s books, particularly An Introduction to the Study of Indian History and The Culture and Civilisation of Ancient India in Historical Outline, remain essential reading for students and scholars. They challenge us to look beyond surface-level events and delve into the economic, social, and cultural undercurrents that define a civilisation. His interdisciplinary methods—combining history with linguistics, archaeology, and ethnography—offer a model for tackling the complexities of India’s past and present.

A Visionary

Damodar Dharmananda Kosambi was more than a historian; he was a visionary who transformed the study of Indian history. By blending Marxist theory with empirical rigour, embracing fieldwork, and adopting an interdisciplinary approach, he reshaped how we understand India’s past. His courage in challenging romanticised narratives and his focus on material conditions and social inequalities make his work as relevant today as it was during his lifetime. As we honour Kosambi on his death anniversary, we celebrate a scholar whose intellectual legacy continues to illuminate the rich, complex tapestry of Indian history.

(Author, a former member of the history faculty at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai, is a known commentator on culture, society and politics.)

4 days, 13 hours ago

4 days, 13 hours ago

[[comment.comment_text]]