The Nationwide “Special Intensive Revision” and Its Future Implications

Every few years, before India heads into another great democratic battle of ballots, the machinery of democracy engages in a quieter, more meticulous process — the updating of the voter list. It is a process without rallies or speeches, yet it shapes who gets to vote and, ultimately, who gets to win. This year, the Election Commission of India (ECI) has undertaken one of the most ambitious such exercises in recent memory — the Special Intensive Revision, commonly known as the SIR.

Spread across twelve major states and union territories, the SIR aims to cleanse, correct, and modernize the country’s electoral rolls. Behind this seemingly routine administrative process lies a far deeper significance. It has the power to influence electoral integrity, political competitiveness, and the very inclusiveness of India’s democratic structure.

For the Election Commission, it is a technical exercise. For political parties, it is a battlefield. And for millions of ordinary citizens, it is a question of whether their right to vote will remain intact when the next election arrives.

Accuracy, Transparency, and Inclusion

The stated goal of the Special Intensive Revision is to ensure that India’s voter lists are accurate, inclusive, and transparent. The Election Commission’s instructions are straightforward: remove fake or duplicate names, add newly eligible voters who have turned eighteen, and delete entries of those who have passed away or moved to another constituency.

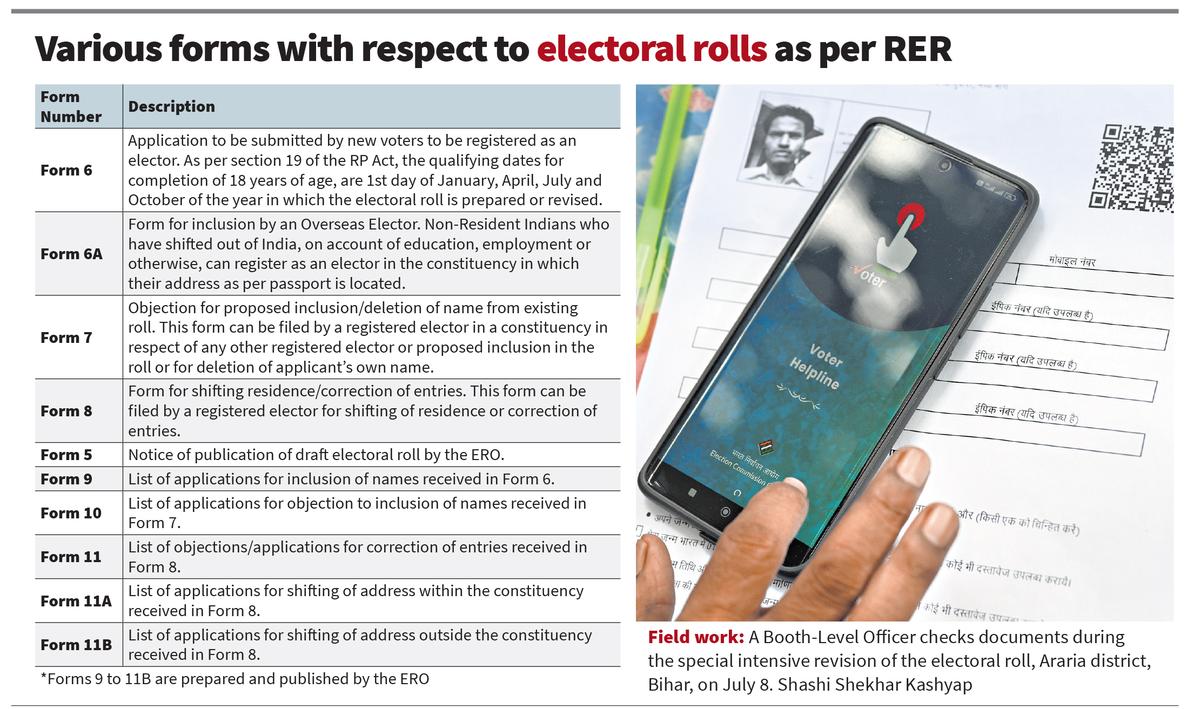

Booth Level Officers (BLOs) are conducting door-to-door verifications, checking documents, cross-verifying details, and updating data through digital platforms. Draft rolls are being published for public scrutiny, after which citizens can file claims and objections.

This combination of field verification and digital processing represents one of the largest civilian data exercises anywhere in the world. Yet, beneath the administrative calm, there are murmurs of anxiety. The inclusion of Aadhaar-based verification, the reliance on mobile data collection, and the compressed deadlines have raised questions about whether speed and technology might be prioritized over accuracy and human judgment.

The authority for such an extensive revision lies in the Representation of the People Act, 1950. Section 21 of the Act empowers the Election Commission to revise electoral rolls “in such manner as it may think fit.” This provides the Commission with broad legal discretion to initiate special revisions when required.

The reasoning behind such provisions is sound. In a country with over 1.4 billion people and unprecedented internal migration, electoral rolls must evolve constantly. People move, die, marry, change addresses, and reach voting age every day. Without periodic special revisions, the rolls would become bloated and unreliable.

However, the law’s flexibility also gives rise to suspicion. In the absence of detailed public communication and third-party oversight, the process can appear opaque. Critics argue that while the ECI’s autonomy is essential, its discretion must always be matched by transparency and accountability.

What makes the current SIR particularly sensitive is its timing. Several states undergoing revision—such as West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Rajasthan—are politically volatile and have upcoming assembly elections. Minor fluctuations in voter lists in these regions could have significant political implications.

In states like Bihar, where a pilot SIR was conducted earlier this year, the process led to a storm of protests. Opposition parties alleged that large numbers of legitimate voters, particularly from marginalized and minority groups, had been arbitrarily removed. The Election Commission later clarified that some errors had occurred at the field level due to miscommunication and inadequate training. Yet the incident left behind a lingering distrust that now shadows the national rollout of the SIR.

For the ruling parties, the revision represents a push toward cleaner rolls and a safeguard against duplicate or fraudulent voting. For the opposition, it is a potential instrument of exclusion. For the Election Commission, the challenge lies in demonstrating that the process remains fair, inclusive, and immune to political manipulation.

Technology and the Digital Challenge

Unlike earlier revisions that relied heavily on paper forms and manual registers, the current SIR is driven by technology. Aadhaar linkage has become the central pillar of verification, allowing authorities to detect duplicates across constituencies. Mobile-based apps now enable BLOs to upload data instantly, geotag visits, and submit real-time updates.

These innovations promise unprecedented accuracy and efficiency, yet they also introduce new vulnerabilities. Citizens without Aadhaar cards, or those with mismatched details, risk exclusion. Connectivity issues in rural areas can lead to incomplete data uploads, while algorithmic duplication filters may wrongly flag genuine entries.

The Election Commission’s task, therefore, is not just technological but ethical — ensuring that technology enhances inclusion rather than erecting new barriers. A database error may be fixable in an office, but for a poor migrant or an elderly villager, it could mean the loss of a vote and the erosion of trust in the system.

India has experienced several roll controversies in the past that continue to shape perceptions today. The voter list irregularities in Assam in the 1990s led to decades of tension around the concept of citizenship, culminating in the National Register of Citizens (NRC). In 2018, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh witnessed allegations of mass deletions linked to data mismatches, which became political flashpoints during their respective elections.

These experiences show that while roll revision is necessary, it must be handled with extraordinary care. Every deletion represents not just an administrative correction but a human story — a citizen’s claim to participation in democracy. Once public trust in the process is damaged, it is difficult to restore.

The Fear of Disenfranchisement

The most profound risk in a large-scale revision is the possibility of exclusion. India’s most mobile and vulnerable populations — migrant workers, urban poor, and marginalized groups — often lack stable addresses or identity documents. For them, verification exercises that depend heavily on documentation can become insurmountable obstacles.

Women who change surnames after marriage, elderly citizens who have outdated documents, or families living in rented accommodations often find themselves in bureaucratic limbo. They are neither intentionally excluded nor easily included. The administrative language of “cleaning the rolls” can, in effect, become a silent act of disenfranchisement for thousands.

The problem is compounded by the lack of awareness. Many citizens do not know how to check their names online or how to file correction forms. In rural and semi-urban areas, the digital divide turns what should be a simple verification process into a bureaucratic labyrinth.

Human Stories and Real Impact

Consider the story of Razia Begum, a 55-year-old domestic worker in Patna, who discovered her name missing from the voter list after years of consistent voting. The local officer told her the Aadhaar number did not match. Razia neither knew how to fix it nor had the resources to seek legal help. Her case, and thousands like it, represents the quiet suffering that often goes unnoticed in discussions of data accuracy and administrative efficiency.

Each missing name is a lost voice in a democracy that prides itself on inclusivity. The moral imperative of the SIR, therefore, is not merely to clean the list but to ensure that no legitimate voter is swept away in the process.

The Election Commission has established several mechanisms to reduce the risk of wrongful deletions. Draft rolls are being made public for inspection both online and at local offices. Citizens are given the opportunity to file claims and objections within specified windows. Political parties are allowed to nominate representatives to monitor the process at different levels.

However, implementation varies widely between states. In some areas, BLOs are overburdened and poorly trained. In others, the communication of procedures to the public remains minimal. The success of the SIR depends as much on administrative efficiency as on citizen participation. Without widespread public engagement, even the most well-intentioned safeguards may fail in practice.

The States Under the Spotlight

The SIR covers a diverse set of regions: West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, Kerala, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Goa, Andaman and Nicobar, Lakshadweep, and Puducherry. Each of these states represents a different demographic and political context.

West Bengal’s high political polarization makes any alteration in the voter list a matter of intense scrutiny. Tamil Nadu’s expanding youth population adds pressure to include first-time voters efficiently. Uttar Pradesh, with its vast electorate, faces the logistical challenge of verifying millions of entries. In Kerala and Rajasthan, where electoral contests are often tight, even small changes in voter rolls could influence outcomes.

In this sense, the SIR is not a uniform exercise but a patchwork of localized challenges, each shaped by its political culture and administrative capacity.

Unsurprisingly, the SIR has sparked political reactions across the spectrum. Opposition parties have accused the government of attempting to engineer the electorate by selectively removing certain voter groups. They point to past errors and inconsistencies as evidence of potential bias.

Ruling parties, on the other hand, have defended the exercise as essential to maintaining the integrity of the electoral system. They argue that a clean voter list benefits everyone and prevents electoral fraud.

Caught in the middle is the Election Commission, whose institutional credibility has often been both its greatest strength and its most delicate asset. Any perceived bias, even if unintentional, can erode decades of hard-earned public trust. The Commission’s conduct during the SIR, therefore, will play a defining role in shaping its reputation before the next general election.

Transparency and Inclusion

If the SIR is to succeed, the Election Commission must ensure a balance between technological precision and human sensitivity. Transparency should be the cornerstone of the process. Regular publication of progress data, detailed explanations for deletions, and open communication about verification procedures can go a long way in restoring confidence.

Public awareness campaigns are equally critical. Citizens must know their rights and responsibilities in this process — where to check their names, how to file corrections, and how to seek redress. In regions with high mobility, extended deadlines and special camps could make the difference between inclusion and exclusion.

Independent audits by credible academic institutions or non-governmental organizations could also serve as confidence-building measures. A transparent, participatory approach will transform the SIR from a bureaucratic formality into a civic movement.

The success of any democratic institution ultimately depends not on its technology but on the trust of its people. A flawless digital roll means little if citizens no longer believe that their names are safe on it. The human element — the compassion of the BLO, the diligence of the local officer, the awareness of the voter — remains at the heart of democracy.

Technology can streamline, but it cannot empathize. The Special Intensive Revision will be remembered not for how swiftly it deleted duplicates but for how gently it preserved dignity.

The Special Intensive Revision is not merely an administrative task; it is a test of democratic maturity. It will reveal whether India can harness technology without sacrificing inclusion, whether efficiency can coexist with fairness, and whether institutions can maintain neutrality amid political storms.

In the end, the question is simple: when the next election day arrives, will every citizen who wishes to vote find their name on the list? If the answer is yes, the SIR will have served its purpose. If not, the loss will be measured not only in votes but in faith — faith in a system that millions once believed could never fail them.

A credible voter roll is the foundation of a credible democracy. In that sense, the SIR is not just about cleaning a list; it is about cleaning the mirror in which India sees itself as a republic of equals.

15 hours ago

15 hours ago

[[comment.comment_text]]