Unsafe School Buildings and Hidden Educational Crisis in U.P.

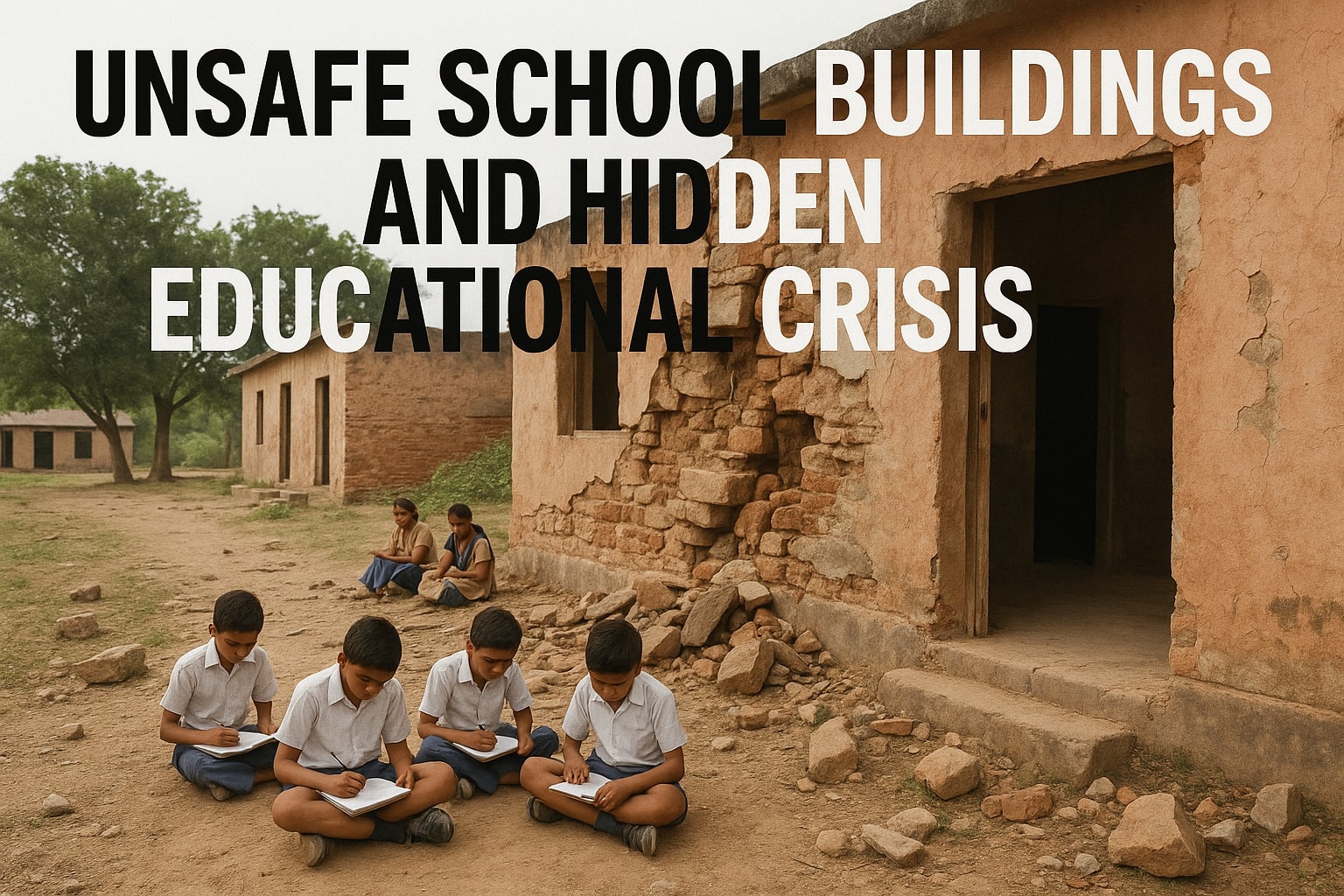

Uttar Pradesh’s revised school merger plan drew headlines for halting closures of schools with over 50 students and ensuring no school stands beyond a kilometer from its community—yet a deeper and more alarming story remains under-addressed: the order to demolish 855 unsafe school buildings, mainly in Shahjahanpur, with scant planning for where students will continue their education or how long new facilities will take to build.

District Magistrate Dharmendra Pratap Singh declared the demolitions non-negotiable, emphasizing immediate removal of structures deemed dangerous. While safety is essential, no clear plan has been shared on relocating students, rescheduling academic sessions, or constructing replacement buildings. The directive mandates written certification from Block Education Officers that these buildings are not in use, but does not specify timelines for new infrastructure or interim arrangements .

Meanwhile, the merger plan threatens thousands of small rural schools across UP. Government records estimate over 26,000 primary schools closed and 5,000 merged, impacting educational access in many communities. This restructuring coincides with over 27,000 rural schools reportedly facing potential shutdown, jeopardizing children already vulnerable to dropouts and inequity.

Critics argue that merger logic—based purely on enrolment thresholds—overlooks systemic weaknesses in infrastructure, teacher absenteeism, and poor facilities that deter attendance to begin with. Thousands of schools lack electricity, toilets, clean water, or midday meals; it is these deficits that drive low enrolment—not indifferent communities.

Yet when it comes to the destruction of 855 campus buildings, there is no discussion of budgets, construction timelines, or even safe alternatives. While officials promise that vacated buildings will become early childhood centers (Bal Vatikas), there’s no indication this applies to demolished campuses. Parents in Shahjahanpur fear sudden displacement of students—especially girls and poor children—with no transport or provisional learning sites provided.

Opposition leaders have escalated the matter. AAP MP Sanjay Singh terms the demolition + merger strategy dangerous, particularly in districts where travel routes expose children to wildlife, hazardous terrain, or railway lines. Samajwadi Party MPs claim the move breaches the Right to Education Act and seeks central government intervention: they warn the state’s focus on commercial enterprises—like opening liquor shops—outpaces its commitment to public schooling.

Although the Allahabad High Court has upheld the merger policy, dismissing petitions on legal grounds and referencing NEP 2020, many argue the court overlooked core issues of accessibility, especially in remote areas. The bench asserted that distances up to 2–2.5 kilometers fall within workable limits—but dismissed concerns for children forced to trek dangerous paths without transportation support.

Educational data paints a grim picture. UDISE+ shows 132,886 government primary schools, but thousands report enrolment under 50 or even zero. Nearly 1.11 lakh schools have only one teacher; many infrastructure audits flagged over 600 schools in Prayagraj alone as unsafe. Against this, UP’s 2025-26 budget of ₹8.08 lakh crore allocates just 13% toward education, equating to ~0.36% of GDP—far below NEP’s 6% target .

Thus the state is running demolition, merger, and reform in parallel—with no transparent plan to ensure children’s continuity of learning. While vacated schools may become child care centers for ages 3–6, there is no policy commitment to ensure older children displaced by demolished buildings return to classrooms once new structures are ready.

On the ground, students and parents report dwindling attendance. Former teachers in schools absorbed into new centers claim dozens of children—especially girls—have simply stopped going to school after the merger. This suggests that consolidation alone cannot sustain inclusive education without better transport, safety guarantees, and functional classrooms.

In essence, UP’s government is pursuing what it calls optimization—yet appears willing to sacrifice education infrastructure without durable planning. If slogans like “Badhega Bharat” and promises of “Bharat banega Shikshit Bharat” are to mean anything, they must go beyond reactive logistics and political damage control.

Schools cannot be treated as expendable real estate—be it for repurposing or demolition—unless alternative arrangements are concretely in place. The scale of the demolitions and mergers demands urgent public accountability: timelines, budgets, building contracts, and educational impact assessments cannot be silent.

Unless there is a transparent roadmap linking demolition to reconstruction and continuity of learning, UP risks turning its education reform narrative into one of neglected rural children, shuttered campuses, and broken promises.

(Writer, a Ph.D. in Sociology, is a well-recognised author and columnist. For past over three decades, he has served in various administrative and academic capacities at Banaras Hindu University.)

3 weeks, 5 days ago

3 weeks, 5 days ago

[[comment.comment_text]]